Part 5 in our series about developmental milestones in early childhood focusing on mobility. See part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 6, part 7, part 8, part 9, part 10, part 11, and part 12. Learn more about the Explorer Mini here.

"When development along any line is restricted, delayed, or distorted, other lines of development are adversely affected as well.” (1)

Restricted experiences and mobility during early childhood can have a diffuse and lasting influence. Long term physical restrictions during infancy or early childhood can significantly alter and disrupt the entire subsequent course of emotional or psychological development in the involved child (2).

Breeding Dependence

Such deprivation of physical and social contingencies can lead to secondary developmental problems, including limiting motivation to explore the environment. This motivation effect is termed learned helplessness, a condition in which the child gives up trying to control his or her own world because of motor disability and diminished expectations of caregivers (3). Butler (1998) also found that children whose mobility is limited during early childhood develop a pattern of apathetic behaviors—specifically a lack of curiosity and initiative. In essence, being deprived of the experience of self-initiated mobility may keep these children dependent.

Breeding Independence

Sound empirical evidence demonstrates that children with disabilities using mobility devices became less dependent on controlling their environment using verbal commands, more interested in the environment and peer interaction (4). By providing a means for self-initiated mobility we are fostering a sense of independence and curiosity. The longer a child is without self-initiated mobility the more profoundly cognitive, social, language and motor skills will be delayed. In other words, if we provide mobility to a young child we may prevent the range of deficits that come with the lack of mobility experience noted above. But if we are considering a 2-year-old that has not had self-initiated mobility we will see a greater array of challenges and difficulties since their lack of control and independence may have led to apathy. Based on this alone, we understand that a trial of the device should start as early as 12 months of age.

Prerequisites

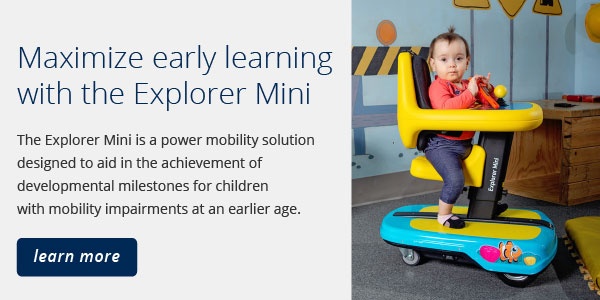

Since the evidence supports that children are less dependent when provided with self-initiated mobility, what are the pre-requisite skills for a young child to trial the Explorer Mini? We know that this device was designed for children who have limited, or no mobility and the device has incorporated the postural support required not only for safety, but to promote freedom of movement, trunk and head control and hands coming to midline. Since the Explorer Mini is the only device of its kind, we don’t have the data to provide specific pre-requisites for use. But we do know what happens with extended periods of immobility for these children. Allowing infants as young as 12 months to trial the Explorer Mini may prevent the learned helplessness and loss of curiosity that can occur with children who have been immobile. Be proactive in providing every opportunity for an infant to achieve self-initiated mobility and contact us here for a trial.

1. Butler, P.B. (1998) A preliminary report on the effectiveness of trunk targeting in achieving independent sitting balance in children with cerebral palsy. Clinical Rehabilitation, 12, 281-293.

2. Butler, P. (1988). High tech tots: Technology for mobility, manipulation, communication, and learning in early childhood. Technology, Infants Young Children, 1, 66-73

3. Weisz JR (1979) Perceived control and learned helplessness among mentally retarded and nonretarded children: a developmental analysis. Developmental Psychology 15(3): 311–9470

4. Paulsson K Christofferson M - 1986 - Psychosocial aspects of technical aids How does independent mobility affect the psychosocial and intellectual development of children with physical disabilities.pdf.

Dr Teresa Plummer, PhD, OTR/L, ATP, CEAS, CAPS

Dr Teresa Plummer, PhD, OTR/L, ATP, CEAS, CAPS

Associate Professor in the School of Occupational Therapy at Belmont University

Dr Teresa Plummer, PhD, OTR/L, ATP, CEAS, CAPS is an Associate Professor in the School of Occupational Therapy at Belmont University in Nashville, TN. She has over 40 yrs of OT experience and 20 in the area of Assistive Technology. She is a member of the International Society of Wheelchair Providers, and the Clinicians Task Force. She is a reviewer for American Journal of OT and guest reviewer for many other journals. She has presented internationally, nationally and regionally particularly in the area of pediatric power mobility. She has authored journal articles and textbook chapters in the area of OT and pediatric mobility and access.